One way of seeing things is that Jesus being crucified was a surprising event. That it was a real pity that the son of God should find himself rejected by the ones he came to. That this was a tragedy which could have been avoided if other, better people had been in charge when he showed up.

This view sees the Romans as really screwed up – they killed the guy they should have listened to. It supposes if Jesus came again, this time maybe to America, he’d be treated better He’d gain a following who would get it, and he wouldn’t be imprisoned by the government, humiliated, and even killed. After all, 62% of Americans say they already believe in Jesus!

You can sort of imagine a video game type scenario in which Jesus enters the world as a baby at various times in history and into various parts of the world. Rome in the first century, Brazil in 1962, Russia in 1993, Spain in 1493, USA in 1889. There is one way of seeing things in which some of these entrances go well. He’s accepted, the movement gains momentum, Christianity is adopted by everyone in the country, and even the government becomes Christian. Mission success!

There is another view, one espoused by Kierkegaard, in which Jesus is never accepted, always disgraced, and that he would be thrown out by every government across all times and places. This is summarized nicely by Immortal Technique in his song “Sign of the Times.”

Imagine the word of God without religious groupies,

Imagine a savior born in a Mexican hooptie,

Persecuted single mother in a modern manger,

You’d crucify him again like a f*****’ stranger,

The first time I remember considering this view was around 2020 – I remember where I was standing. Consider with me the words of Søren Kierkegaard writing in the mid 1800s from Denmark.

“The crowd is untruth. Therefore was Christ crucified, because he, even though he addressed himself to all, would not have to do with the crowd, because he would not in any way let a crowd help him, because he in this respect absolutely pushed away, would not found a party, or allow balloting, but would be what he was, the truth, which relates itself to the single individual.“

Kierkegaard suggests that Christ came to the world and “addressed himself to all,” and yet he wanted no part of becoming popular or winning favor with large groups of people. This view is a direct challenge to the one which sees Jesus as coming to preach as many good sermons as he could and build as big a following as he could so that one day everyone on earth would be a Christian as the movement spread bigger and bigger. Kierkegaard claims that Jesus “pushed away” and actively rejected attempts to make him a political figure who gained influence through being accepted. This runs totally counter to the modern evangelistic perspective that it was Jesus’ (and should be our) goal to convert as many souls as possible through clear teaching and persuasive words. Consider John’s account:

“On hearing it, many of his disciples said, “This is a hard teaching. Who can accept it?” Aware that his disciples were grumbling about this, Jesus said to them, “Does this offend you?…From this time many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him. (John 6)

The gospel of Matthew records:

And the disciples came and said to Him, “Why do You speak to them in parables?” Jesus answered them, “To you it has been granted to know the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been granted. For whoever has, to him more shall be given, and he will have an abundance; but whoever does not have, even what he has shall be taken away from him. Therefore I speak to them in parables; because while seeing they do not see, and while hearing they do not hear, nor do they understand. (Matthew 13)

Jesus’ strategy is to speak in veiled ways, using parables and sometimes very confusing stories when speaking to crowds. His own disciples often don’t even understand what he’s saying. Jesus will then explain the meaning once the crowd is gone and he is alone with the twelve. If the idea is to spread the message and get the crowds on board, you’d think the son of God would have a better game plan. Kierkegaard claims that Jesus didn’t want the acceptance or help of the crowds, that he was doing this on purpose. The decision to accept the teaching therefore had to be an individual one, not one along with the crowd.

There is a view of life which holds that where the crowd is, the truth is also, that it is a need in truth itself, that it must have the crowd on its side. There is another view of life; which holds that wherever the crowd is, there is untruth, so that, for a moment to carry the matter out to its farthest conclusion, even if every individual possessed the truth in private, yet if they came together into a crowd (so that “the crowd” received any decisive, voting, noisy, audible importance), untruth would at once be let in.

Here, Kierkegaard goes a step further. Not only is Jesus not interested in gaining approval from the crowd as his strategy, Kierkegaard says there is a “view of life” in which wherever the crowd is, there is untruth. This is to say that if you want a sure-fire way to get the “untruth,” hold yourself an election and see what the crowd decides. What is most popular is always the un-truth. The truth is that which is never collectively accepted.

Where the crowd is, therefore, or where a decisive importance is attached to the fact that there is a crowd, there no one is working, living, and striving for the highest end, but only for this or that earthly end; since the eternal, the decisive, can only be worked for where there is one; and to become this by oneself, which all can do, is to will to allow God to help you – “the crowd” is untruth.

I think the context in which Kierkegaard is writing, 19th century Denmark, makes his work all the more relevant to the modern American reader. Kierkegaard was writing to a society in which virtually everyone said they were Christian – even the government was Christian. Aaron Edwards describes Kierkegaard as a “missionary to Christendom” saying, “he came to re-emphasize precisely what this ‘Christian’ society was supposed to have known all along and yet did not seem to know at all.” In his thesis paper, Robert Jones describes Christianity in Kierkegaard’s Denmark saying “For most people at the time, becoming a Christian was not a matter of faith but more so a matter of being born to Christian parents, observing the religious rituals, and getting a feeling of solidarity from church attendance. This was especially true of the Protestant Lutheran churchgoers in Denmark, who were also required to be members of the State Church.” Kierkegaard became known as a vicious critic of this church which he viewed as stale, lifeless, and even predatory.

To me, this seems deeply relevant considering the state of the American church and society. Our leaders constantly invoke Christian language. Consider the recent post made by the Department of Homeland Security which pairs scripture from Isaiah with images of soldiers in full battle rattle hunting down immigrants. The current presidential administration has declared they are “bringing religion back,” and while I have no idea what that means, it is indicative of a state that openly embraces Christian language. Doing so certainly gains them popularity points in a nation where 62% of people and 72% of 2024 Trump-Vance voters say they are Christian. This is certainly not new and US presidents have long invoked faith in God and scripture as they carry out their agendas. Particularly striking was the president’s recent faith-laced language while dropping bombs:

“And I want to just thank everybody, and in particular, God. I want to just say we love you, God, and we love our great military. Protect them.” (source). Trump’s tweets are often similarly laced with appeals to Christianity and faith and his speeches do so “at a higher rate than any president in the last 100 years.” He knows who he’s talking to.

“The crowd is untruth. There is therefore no one who has more contempt for what it is to be a human being than those who make it their profession to lead the crowd.“

It is perhaps no secret that I have no admiration for our current president. And I do not consider myself a part of the “Christian” he talks about. But more importantly for this conversation, I do not consider myself part of the “Christian” which could be proclaimed from the office of any nation’s president, liberal or conservative or in-between.

I think Kierkegaard is right – the crowd is untruth. The state, the government always rejects and tramples on the son of God. The light comes into the world, and it is always rejected by the masses. Not once way back when in a fluke, when backwards people missed it. No. The power of the gospel, the kingdom of the heavens, this is always rejected by those whom it does not serve – these are the rich, those in political power, the state. It is good news to a few, to a minority, to some outliers. We currently see the rich and powerful co-opting the words of scripture to try and appeal to the masses, the poor, and their voters. This is the untruth.

To take Jesus and his teaching seriously is not a good political strategy. It does not allow for the accumulation of political power, oppression of the poor, violent or coercive use of force, or really any of the things required to run a government. So when I hear the richest, most powerful, most armed-to-the-teeth government in the world clucking on about faith and God, it means nothing. To accept the kingdom of God and the way of Jesus would literally be their undoing.

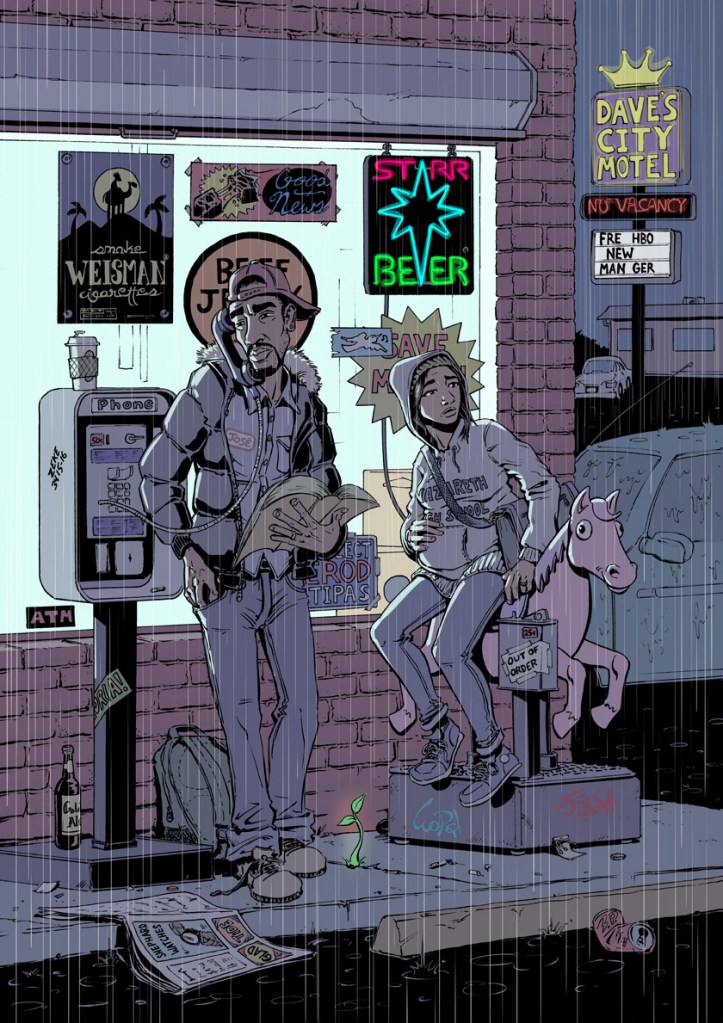

I was moved when I recently saw the below image from Everette Patterson titled “José y Maria.” He says it is “depicting Jesus’s parents in a modern setting.” Ours is a world where Jesus was given a sham trial and crucified by the mob. And ours is a world where our neighbors are being rounded up and brutally deported without even sham trials, where “Alligator Alcatraz” is a real prison camp, and where our tax dollars are spent on bombs to wipe out a brutalized, starving population in Gaza. Ours is a world where the crowd is the untruth and where the kingdom of the heavens is between the cracks, not on the billboards.

Kierkegaard quotes taken from: “That Single Individual” – Soren Kierkegaard