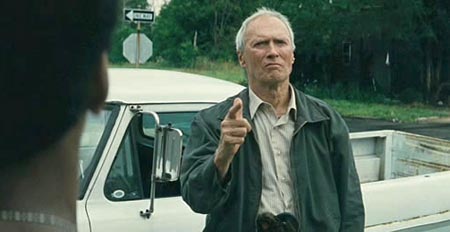

“I finish things; that’s what I do, and I’m going it alone.”

Walt Kowalski (Clint Eastwood) is a tall, white-haired, racist veteran of the Korean War trying to make sense of a changing America. The enjoyment he once found sharing his neighborhood with white folks has morphed into abjectly watching Hmong immigrants invade the homes around him. Faithful dog on one side and case of Pabst Blue Ribbon on the other, Walt is the weathered remnant of an America gone by. And while he’s a man who hates change, it’s ultimately the unfamiliar which serves as the gateway to his transformation and absolution.

Gran Torino is nicely characterized as a melodrama, but it also resembles both a western and a post-Vietnam war film. Director Clint Eastwood has worked on war films (American Sniper), westerns (Unforgiven), and dramas (Million Dollar Baby). With more than thirty films under his belt as a director, Eastwood is well equipped to pull off Gran Torino, a war film without a single scene of battle, a western set in a middle class Michigan neighborhood, a melodrama culminating with a gunfight. However you wish to categorize Gran Torino, it’s a work which stands out in Eastwood’s filmography. The feature has won multiple awards and is the first mainstream American film to cast Hmong Americans in primary roles.

My most vivid experience with an Eastwood film up to this point was Unforgiven, and the similarities between the two films are striking. Gran Torino’s main character, Walt Kowalski, and Unforgiven’s William Munny (also played by Eastwood) are both gunslingers living on the fringes of society, men whose sense of right and wrong won’t let them integrate into the mainstream. Undoubtedly, Eastwood is playing a western character in both of these films – a weathered, experienced fighter who speaks low and evenly. We’re familiar with this character in the context of a western, but I was interested to see what he’d look like living in the suburbs of Michigan.

The film wastes no time in acquainting the viewer with its protagonist. We see Walt in a church standing beside his wife’s casket and grimacing at the presence of his emotionally indifferent family. Time and again, his own sons disappoint him; they only call to ask for favors, visit to weasel deeper into the will, and push pamphlets for nursing homes. The glory of serving his country has long worn off, his wife is gone, and there never was much emotional connection with his family. Walt drives a square body American-made truck and owns a beautiful 1972 Ford Gran Torino, which he helped assemble on the line in the Ford factory. He buys American. He drinks Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. He protects his yard with a carbine rifle from his days in service. And now, he is resigned to sitting on his porch, waiting to die alone, in a neighborhood being claimed by Hmong immigrants.

In the first act, Walt’s commitment to defending his own territory requires him to pull a gun on a gang harassing his Hmong neighbors. The old man finds himself a celebrated hero of the Hmong community. Though at first Walt is resentful of the interaction with his no longer white neighbors, he’s slowly won over by Sue (Ahney Her), a teenage Hmong girl who pursues his friendship, invites him to a party, and even gets him to drink rice liquor. This is the friendship that will lead to Walt’s own transformation. Scene by scene, he acknowledges the honor of his position as neighborhood protector and eventually becomes a sort of grandfather.

Behind his unapologetic demeanor, Walt is tortured by what he later confesses as four sins: avoiding taxes on a boat motor, kissing a woman not his wife, failing to connect with his sons, and, chief of them all, killing a young Korean boy who was trying to surrender. Compounding his shame is the silver star sitting in a chest in his basement. He was decorated for the killing, and the memory of taking the life of a Korean boy haunts him every day. After being harassed, a young Hmong boy named Thao (Bee Vang) seeks revenge and asks Walt what it’s like to kill someone. Walt’s response crystallizes as one of the film’s main thrusts: “It’s goddamn awful – the only thing that’s worse is gettin’ a medal of valor for killing some poor kid who wanted to just give up.”

Even while he’s tormented with guilt, Walt hates the prospect of going to confession. He is particularly opposed to being ministered to by Father Janovich, “a boy fresh out of seminary.” The young priest (Christopher Carley) pursues Walt the entirety of the film, in accordance with the wishes of his late wife. The irony of a young man trying to teach an old war veteran about life and death isn’t lost on Walt. Like the next-door neighbors, the priest does make some headway and even earns the privilege of addressing the old man as “Walt” instead of “Mr. Kowalski” after sharing a beer with him. When Father Janovich finally sits across from Walt in the confession booth, what he hears shocks him. He’s left with the reality that the redemption Walt Kowalski needs is beyond what he can prescribe.

Gran Torino is ultimately about absolution, about the redemption of a soul all but gone. The tension lies in the space between the Walt in act one and the Walt in act three. He must be transformed from a man who would shoot a neighbor crossing the boundary line into a grandfather who will sacrifice himself, from the soldier who killed a helpless Asian boy to a man who dies on his behalf. The question addressed by Gran Torino is, what can initiate that forgiveness and transformation? The efforts of church and family will not be enough – in the end, only the genuine and unreciprocated love of a young Hmong girl will be enough to break through.

In Eastwood’s western Unforgiven, the catalyst for act three is the news of death. When a messenger girl tells Will Munny his partner has been shot, he gives up his sobriety, takes a long pull of liquor, and executes a ruthless vengeance. The same scene happens in Gran Torino. Walt watches his best friend Sue come through the door; her eyes are swollen, her face battered, and blood is dripping down her legs. She’s been raped and beaten by a gang of thugs. Walt drops the glass of liquor in his hand, and the shattering glass is the gavel of judgement from a man who finishes things.

The difference is that in this scene Walt walks toward the evil with the full intent to give his life as a ransom. With a single deft movement and the words “Hail Mary, full of grace,” Walt takes the full force of the evil onto himself. This is an act of judgment, as he condemns the gangbangers to live with his blood on their souls. But, more importantly, it’s his absolution.Walt has been transformed. He’s still a cussing, strong-willed old man with a racist vocabulary, but he’s crossed from killer of the helpless to defender of the innocent.

Gran Torino manages to communicate more about war than many films devoted to the genre, and it does so without ever showing a battlefield. By using dramatic force, this film poses question of life and death, guilt and absolution, within the context of everyday life. It demonstrates the power of formative experience and boldly claims that humanity can overcome the sins of its youth. A man can travel full circle from his front porch in Michigan, from guilt to grace, from death to life. Gran Torino is as hopeful as it is troubling, and there’s plenty of trouble to go around.